Clay Lump

A Guide to This Traditional East Anglian Building Material

Clay lump is an enduring and fascinating form of vernacular construction, unique to East Anglia and predominantly found in Norfolk and Suffolk, though we have also come across it in Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire. A cousin to cob, found in the West Country, clay lump reflects the ingenuity of local builders who made use of the region’s abundant natural resources—clay-rich earth, straw, and even animal dung—to produce functional and sustainable buildings.

In this article, we will explore what clay lump is, how it was historically used, the common issues it faces, and how to approach its repair and preservation in a way that respects its heritage.

What is Clay Lump?

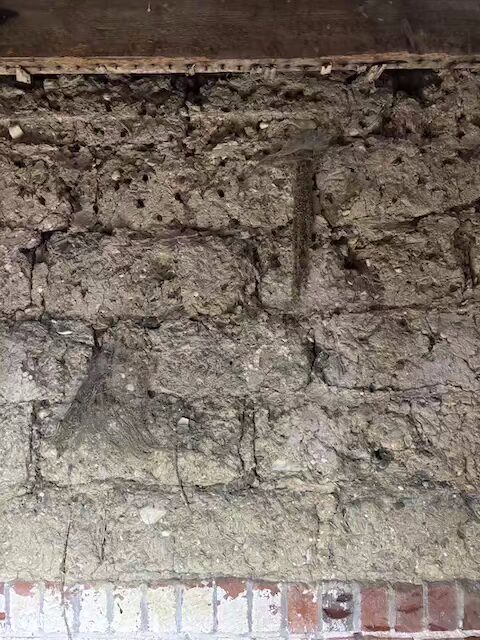

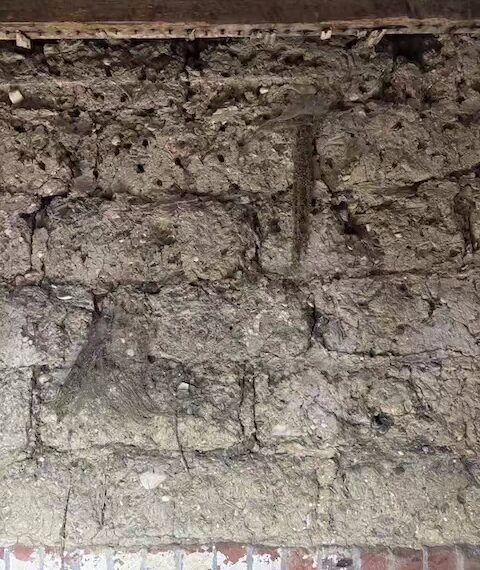

Clay lump refers to large, unfired earth blocks created by mixing clay-rich soil with chopped straw (and sometimes chalk, flint, or dung). This mixture was shaped into rectangular bricks using simple wooden moulds and then left to air-dry. Unlike modern bricks, clay lumps are significantly larger, with typical dimensions ranging from 18 x 6 x 6 inches to 22 x 12 x 5 inches.

The blocks were traditionally laid in clay mortar rather than lime or cement, keeping construction both cost-effective and locally sourced. To provide a stable foundation, walls were often built atop low brick or flint plinths, ensuring the clay lump remained dry and free from rising damp. A tell-tale sign that a building is constructed of clay lump is the presence of a flint plinth, but sometimes the plinths have been rebuilt or covered with render; therefore, it is not always easy to spot a clay lump building!

Externally, clay lump walls were finished with either clay or lime renders. Limewash was commonly applied to add colour, breathability, and weather resistance, while tar was sometimes used as a protective coating. Clay lump buildings were not left exposed as they would quickly deteriorate, but you may see some exposed clay lump agricultural/outbuildings when driving round the countryside of Norfolk and Suffolk, usually because the previous render fell off/deteriorated.

A Brief History of Clay Lump

Clay lump construction emerged in East Anglia in the late 18th century and gained popularity in the early 19th century, particularly during the period when a brick tax (1784–1850) made fired bricks prohibitively expensive. While this construction method resembles the adobe found in Spain and parts of the Americas, clay lump developed as a distinct response to the region’s clayland terrain and agricultural economy.

The origins of clay lump in England can be linked to an earlier version known as ‘clay bats,’ which were thinner but otherwise similar. These were initially used for building dovecote nest-boxes in the late 18th century. By 1791, clay bats were being used to construct cottages in Cambridgeshire. By 1821, the blocks had become deeper and were referred to as ‘clay lumps’.

The building technique became synonymous with cottages, barns, and other modest structures, particularly in Norfolk and Suffolk, where rural builders embraced its practicality and affordability. Advocates such as architects Clough Williams-Ellis and G.J. Skipper revived interest in clay lump construction during the early 20th century, though its use gradually declined with the advent of modern building materials.

The Challenges Faced by Clay Lump

While clay lump buildings have stood the test of time, their longevity relies heavily on appropriate care and maintenance. The most common issues include:

Moisture and Damp

Clay lump is highly sensitive to moisture. As its strength depends on a low water content, excessive damp can cause blocks to weaken and walls to collapse. Modern cement renders and impervious paints trap moisture within the walls, accelerating deterioration to the clay lump.

Inappropriate Repairs

Inappropriate patch repairs using cement or concrete blockwork are common but harmful. Cement’s rigidity and inability to “breathe” can cause thermal cracking, while trapped moisture accumulates and undermines the wall’s integrity.

Structural Issues

Clay lump walls may develop cracks as they dry, though these are usually harmless. However, significant damage from settlement, rodents, or long-term neglect can create voids and instability within walls.

Repairing and Maintaining Clay Lump

Address Damp Effectively

Improve land drainage around the building to prevent water ingress. Ensure paving/concrete does not extend right up to the base of the walls and that there is sufficient surface water drainage.

Ensure the ground levels are a good distance below the internal floor levels. High ground levels will cause damp internally.

Ensure the plinths are free from any non-vapour permeable materials such as cement mortar, cement render, and masonry paints.

Repairs

Use earth or lime-based renders to patch minor cracks. These materials can be mixed with straw to match the original construction.

For repairing large voids or structural failures: Rebuild sections using new clay lump blocks or cob blocks, laid in clay mortar. For very large repairs, work in layers, allowing each lift to dry before adding the next.

Retain Character

Clay lump walls are rarely perfectly straight or uniform. When rendering, it’s important to retain the subtle contours and texture of the original construction rather than imposing a modern, overly smooth finish.

Buying a Building Constructed of Clay Lump

If you are in the process of purchasing a clay lump property, we would advise you to get a detailed building survey so that the materials on the clay lump can be assessed. If the clay lump is covered in non-vapour permeable materials e.g. cement render, then a careful assessment needs to be carried out on the urgency of the removal of those materials. We have good experience with surveying clay lump buildings. Similarly if you already own a clay lump building and are concerned about its condition, then we would recommend a survey.

Conclusion

By avoiding inappropriate repairs, addressing moisture issues, and using traditional materials such as lime renders and clay-based mortars, clay lump buildings can be preserved for the long term.

Scott Enders